Buried under the news regarding county chiefs meeting to discuss the future of The Hundred was a press release by the ECB saying that Sir Andrew Strauss would be leaving his roles as Strategic Adviser to the ECB Board and Chair of the Performance Cricket Committee.

Being Outside Cricket has often been pigeonholed as a ‘Cook-hating blog’. Without speaking for the other writers here, I never hated or even disliked Sir Alastair Cook on any kind of personal level. I didn’t rate him as a captain, feeling that he was ineffectual on the field and dominated by stronger personalities behind the scenes. I absolutely loved him as a batter though. Him and Trott annoying the hell out of opposition bowlers just by refusing to get out represent some of my happiest experiences watching Test cricket. I’d make similar (although perhaps slightly less pronounced) criticisms of Root’s time in charge. In fact, in terms of captaincy, I’m coming closer to the viewpoint that it may well be worth selecting ‘specialist captains’ in the same way you would do with wicketkeepers. Rarely is your best senior batter also the best available leader. More recently, the charge has been levelled that we hate Zak Crawley. Again, my only criticism is that he’s doing a job which he currently seems unable to handle. That’s not his fault, but the fault of those people who are putting him in that situation. He’s clearly trying his best, what’s to dislike?

Sir Andrew Strauss is a different story. ‘Hate’ is too a strong word, but I do not like or even particularly respect him as a person.

I never particularly warmed to him as a commentator, although I’d concede he at least wasn’t as bad as KP or Vaughan. Once Strauss moved back to the ECB as Director Of Cricket, one of his first decisions was to bar Kevin Pietersen from playing for England ever again, which I disagreed with purely on the grounds that the white ball teams at the time didn’t have the strength or depth of batting ability that they do now and it diminished their chances of winning competitions.

The moment I went from disagreeing with his decisions to actively disliking him was 22 April 2018. Specifically, the day he went on BBC radio (and many other platforms/outlets) to launch The Hundred. To be clear, that isn’t the reason. I don’t ‘hate’ The Hundred, even though I have written an ungodly amount on the subject. I just think it was poorly conceived and has been poorly run. Rather, I found Strauss’s words on the subject to be both sexist and condescending to non-cricket fans. I even wrote about it at the time.

Another thing he does which prompts a visceral negative reaction from me is how he presents himself as a stereotypical executive. I suspect the reason Strauss and Tom Harrison were so close at the ECB is that Strauss wanted to be just like Harrison. They both dress the same, both speak in interminable business jargon, and both launched huge, expensive, undeliverable projects at the ECB then left before they inevitably failed. I detest that kind of person. I swear, just hearing the word ‘stakeholders’ makes my blood pressure skyrocket.

Despite posting this on a what has been described as a “hater’s blog”, I do feel like I have to justify why I don’t like Sir Andrew Strauss. Whilst I could pick out snippets from the past several years, there is an easier way. Strauss was invited by the MCC to deliver this year’s Colin Cowdrey Spirit Of Cricket lecture in February. What followed was 30 minutes of insulting English cricket fans, minimising the issue of racism in English cricket, underselling the achievements of the women’s game, misrepresenting the past and present, and presenting a dystopic future where everyone in English cricket are begging billionaires to maybe not screw them over as something to look forward to. I’m not even kidding here.

And so, without further ado, I present a transcript of most of his speech, plus my own thoughts on what he said.

“It does feel a little strange, standing here in front of you all. Perhaps it’s my own warped self-perception but I really don’t feel old enough, or for that matter wise enough, to be lecturing all the dignitaries in the room tonight about anything. Instead, I simply hope to have a conversation with all of you…”

As is typical for conversations with people from the ECB, they are doing all of the talking and we are expected to do all of the listening.

“Before we get going, I’d like to ask you a couple of questions. Does anyone in this room remember any significant event from 16th November 2021? […] Does anyone remember, for instance, on that day the Government announced a plan to require a vaccine booster in order to get a COVID pass? Remember that? Or that the Governor of the Bank Of England expressed concerns that inflation might head above the heady heights of 5% in the months ahead? Seems like a lifetime ago, doesn’t it? Well, I notice from the vacant looks on all your faces that these occurrences do not come easily to mind, which is excellent news to me because this is also the date of the last Cowdrey lecture delivered by the extraordinary Stephen Fry in what must surely be one of the most articulate, well thought-out and erudite performances I have ever witnessed.”

Funnily enough, I immediately remembered a significant event from Tuesday 16th November 2021. In fact, I had to check that I had the correct date when Sir Andrew Strauss completely ignored this particular event, perhaps the most seismic event in the history of the ECB. On that day, just a few hours before Stephen Fry delivered his Cowdrey Lecture to the MCC, Azeem Rafiq was at Westminster for his first hearing in front of the DCMS parliamentary committee. He was immediately followed by representatives from Yorkshire CCC and the ECB, who managed to confirm the worst fears of everyone involved with regards to how English cricket is run.

It is very strange that Sir Andrew Strauss forgot about this because Stephen Fry’s lecture began by referencing the hearings earlier that day. Fry’s opening remarks in 2021 might well have provided a guide for how Strauss could have chosen to approach this lecture, and the issues it raised.

“While being asked to deliver this lecture is a terrific honour, fate has seen to it that it is an honour which comes with a venomous sting in its tail. How characteristic it is of what Thomas Hardy called ‘life’s little ironies’ that I should address you at a time when we should happily be caught between the celebration of a mesmerising Men’s T20 World Cup and the mouth-watering promise of the 72nd men’s Ashes in Australia. Instead, I find myself having to give this talk from inside the choking miasma of one of those unsavoury and shameful scandals that regularly seems to engulf the game that we love. The mephitic stink that arose from Yorkshire two weeks ago is being smelled around the world, and has done no favours to that club, nor to the reputation of cricket or this country. In the midst of this stench, do we now need another ageing, white, male, from the heart of the establishment to lecture us in plummy tones on the spirit of cricket?”

It is also very on-brand for the MCC to consider the question Stephen Fry asked and then get someone who precisely fits that description for the next one. Given every possible opportunity, the MCC will never knowingly miss the chance to act exactly like a caricature of an aloof 19th century aristocrat.

“I think it is worth taking a minute to step back and ask ourselves a potentially more fundamental question: What is cricket for? What is the purpose of cricket? What are we hoping by playing or supporting the game? If we’re in the ECB offices next door, we might be asking what are the KPIs [Key Performance Indicators] to ensure we are achieving our ambition with regards to the game. I sense the odd eye rolling on that one, but one thing we know for sure is that those early pioneers of the game in the 1600s, most likely somewhere in the South of England, would not have been in possession of a policy document with KPIs written on it. It’s worth asking for a moment however, what they were trying to achieve with their underarm bowling and strangely curved bats.

Of course, we will never know the answer to this, but I can only hazard a guess that they were attempting to do three extremely simple but hugely important things. I sense they were using the game as a way of connecting people. In essence, bringing together wherever they were from and whatever their backgrounds to form a community of those with a shared interest. Alongside this, they were intent on creating entertainment for themselves and others, in what must have been an extraordinarily mundane rural lifestyle. Alternative activities and pursuits were thin on the ground back then. There was no Instagram. Finally, as people started to gather to watch these spectacles, I suspect that they would have been mightily enjoying seeing the engagement in the game. Whether that be the little boys and girls with their boundless energy simulating the efforts of those out in the field of battle or those in the latter stages of life enjoying the fresh air and the opportunity to meet and chat about the action on the field alongside other issues of the day in the comfort of a wooden seat or picnic blanket. Three simple but incredibly powerful areas of ambition. To connect, to entertain, and to engage.”

Whilst I am perfectly willing to concede that I am no historian, and honestly have little interest in the subject (I am more concerned with the here and now), very little of this section rings true to me. The idea that cricket has historically been a force for unifying communities and people of differing backgrounds in England defies even casual inspection. The MCC and first class counties encouraged and enforced a division between wealthy amateurs and the financially-dependent professionals from their creation until the abolition of amateur status in 1963. This was no theoretical divide. It was not until 1952 that Len Hutton became England’s first ‘professional’ captain, and both Surrey and Lancashire did not have a professional captain until 1963. Whilst things have improved since then, family wealth still plays a significant role in whether someone can reach the highest echelons of cricket both on and off the field. And all of that is before we consider English cricket’s treatment of women, Black and Asian cricketers in both the past and present.

The rest seems to be nostalgia for a past that never (or rarely) existed. The idea that people in centuries past were bored all of the time is highly patronising and demonstrably false. People have been entertaining themselves for millennia, without the help of cricket or any other modern innovations. If I were to suggest to an old man like Chris (aka thelegglance) that his early life must have been dull and meaningless before the invention of television or Twitter to keep him entertained, he would quite rightly tell me to sod off. Or words to that effect.

Cricket is not, nor has it ever really been, a solely rural pursuit. We know this for one very simple reason: Where are all the professional cricket grounds? With a few exceptions, they are all in city and town centres. Likewise, the stereotypical view of cricket as being watched by young children and the elderly is a telling mistake. Outside of the last 25-30 years, the top levels of English cricket were predominantly funded by the sale of tickets. Therefore, a large proportion of attendees would invariably be people of working age who could afford to buy those tickets.

“In my formative years as a cricketer playing for Radley College, Oxfordshire and Middlesex in the 1990s, the formidable Australian team reigned supreme. It was perhaps the most successful team in the history of the game. They were a juggernaut that smashed its way through any obstacle in their way with a swagger and a confidence that might never be seen again. To my eyes then, it’s clear what cricket is about. It was about winning. It was about being ruthless. It was about exploiting weaknesses and finding ways to mentally disintegrate opposition teams. In England, we looked on at those all-conquering Aussies with a mixture of awe and envy. The whole of the English games attempted, largely unsuccessfully I might add, to emulate this naked aggression. On the county circuits in the late 90s and early 2000s, the Spirit Of Cricket was largely frowned upon by coaches and captains. No more Mr. Nice Guy was the order of the day. The Spirit Of Cricket in this period, while perhaps not of a mean disposition, was relegated mainly to the sub’s bench, or the dressing room, or the bar once proceedings on the field had finished. On the field, you sense that the ends often justified the means.

I always found myself somewhat internally conflicted with this collective mindset. On the one hand, as an opening batsman facing the likes of Brett Lee and Shoaib Akhtar, I knew that (as Colin Cowdrey had pointed out) you had to be tough and resilient and up for the challenge. But on the other hand, I didn’t particularly warm to the naked masculinity of it all. I dealt with a lot of that playing rugby at Durham University and it was one of the reasons I focussed my attention on cricket. Cricket was a bit more relaxed, it was fun and laissez-faire, and it was more inclusive than many different characters and mindsets.”

It is easy to forget that Sir Andrew Strauss published the High Performance Review featuring his recommendations for improving English cricket less than five months ago. Or, at the very least, Strauss must think it is easy to forget since much of his speech contradicts both the specific contents and broader foundations of that report. The central premise of the exercise, led by Strauss, was that the entirety of English cricket should all be aligned behind a win-at-all costs (‘costs’ referring to both cash and wider consequences) mentality. “What It Takes To Win”, to borrow the term favoured in the report.

Rather than celebrating the uniqueness of English cricketing culture, Strauss’s review explicitly sought to replace it with the cut-throat attitudes from other sports. This began with the people he chose to co-author the report, which included two Premier League directors and former British Cycling director Sir Dave Brailsford. The latter’s tenure in charge of the British Olympic squad and Team Sky would certainly not be described as ‘relaxed, fun and laissez-faire’ by anyone. The proposals they suggested included creating a new ECB committee of people from outside cricket (I enjoy the irony in this), meaning other sports and the world of business, to offer their insights regarding how English cricket and its teams should be run.

“What is the game of cricket for today? Why do we play the game now, and whose interests should it represent? Is the purpose of the game today still aligned to the ambitions of those early pioneers or has it moved on to a very different place now the underarm bowling and curved bats have been replaced with doosras and switch hits? Well, as I get older and perhaps less saturated in the extraordinary pressure-filled bubble that envelopes you as an international player, the answer to that question becomes more and more clear. To me, the game of cricket can’t just be about winning or, as many people paint it out, to be about pounds and pence, dollars and quarters. No. The game continues to be about bringing people together from different backgrounds and experiences. It remains about binding countries together, often with complicated and acrimonious histories. It’s about serving as a great educator about discipline, and patience, teamwork, and surrendering to something bigger than yourself. And finally, it’s about doing it all with a smile on your face and providing entertainment, something the late Colin Cowdrey was so famous for. In short: The purpose of the game for me remains to serve those three important prongs. It’s about connecting, entertaining and engaging people.

The more I think about it, my belief that this purpose of the game has never and hopefully will never change.”

The final line in this section is the real kicker for me. As well as representing a Damascene conversion from his own High Performance Review not five months earlier, this lecture also fails to be consistent within its thirty-minute duration. For now, just remember the line “the game of cricket can’t just be about winning or, as many people paint it out, to be about pounds and pence, dollars and quarters”.

“The coming together of Brendon McCullum and Ben Stokes in May last year has shifted the game of cricket from its foundations and has asked some fundamental questions of the centuries-old accepted truths of the Test format. ‘If in doubt, bat first’ has been replaced by ‘I want to chase in the 4th innings. We can chase anything’. ‘Build an innings’ has been replaced by ‘shoot first and ask questions later’. ‘See off the new ball’ has been replaced by ‘Hit it harder’. And ‘bowl maidens and apply pressure’ has been replaced by ‘forget about the scoreboard and just find a way to induce a mistake’.”

I do wonder what Brendon McCullum and Ben Stokes think of this fairly one-dimensional description of their approach by the person who was ultimately their boss as director of the ECB’s Performance Cricket Committee. Certainly both the batting and bowling has been more aggressive since Stokes became captain, but that has in large part coincided with playing in batting-friendly conditions where it has been both easier to score runs and more difficult to take wickets. Matches where the opposition bowlers were on top, such as during the series against South Africa, saw England become more circumspect as a result.

It’s also odd to see ‘bowl maidens and apply pressure’ as being centuries-old wisdom. I distinctly remember David Saker introducing the concept of ‘bowling dry’ to the England team in the 2010-11 Ashes. The conventional wisdom, or at least the wishes of most cricket fans I had conversations with, was always that England’s bowlers should bowl at the stumps more often with an aggressive field even if that led to conceding more runs in the short term. The idea that this therefore represents a groundbreaking innovation in cricket amuses me.

“They [McCullum and Stokes] are in turn challenging all of us who love the game, no matter what our preferences, to look inward and question our own prejudices. If your preferred tipple is the Test format, or is that because of or despite the slow, meandering nature of the contest. Does adding a little extra spice and dynamism into the game make it better to watch? I think the answer to that question is yes. And if you have trekked up from the traditional heartlands of the game to the heady altitudes of the IPL and franchise cricket, or for that matter never descended from those heights in the first place, are you perhaps better connected with the Test format on the back of England rollicking along at 7 runs an over?

A distinct fault line between the red and white ball games, so often protected fiercely by specially trained and thoroughly indoctrinated border guards are now not looking quite so impregnable. The proverbial Berlin Wall between the formats is crumbling before our eyes.”

One thing you might notice when listening to players, administrators and pundits (with Sir Andrew Strauss having been all three), is that they often lack any understanding of why cricket fans might prefer Test cricket over the other formats. They have spent most of their professional lives within a bubble where they spend a lot more time with each other than those of us who ultimately pay their wages. I would struggle to find a single person who said that a slow scoring rate in its own right was something they liked about Test cricket. That isn’t to say that I don’t enjoy passages where not many runs are scored, but this is because it often occurs when the bowlers are bowling well or conditions are in their favour and the batters are being tested as a result. The clue is in the name. It is (or should be) a Test.

One obvious benefit Test cricket has over T20 is sheer duration. Why would I want to see Jofra Archer bowl just four overs in a day when I could watch him bowl fifteen? Or see Joe Root bat for half an hour instead of all day? I also really enjoy watching sports where specialist position players have to participate in areas they aren’t as good at, in the way that bowlers always have to bat in Test cricket. I honestly haven’t watched a single game of baseball since the National League changed its rules to stop pitchers having to bat instead of Designated Hitters. In T20s, it is pretty rare for the three worst batters in the team even have to pad up. Finally, I personally find that Test cricket lacks the artificiality of T20s. There are minimal fielding restrictions, no limits on the number of overs a team’s best bowlers can deliver, and a time limit which usually doesn’t affect the outcome of the match. When something exciting happens in a Test match, it feels more real than when you have powerplays, fireworks, and a commentator shouting in your ear every few minutes.

This is a running theme through this lecture by Strauss, but I do find it slightly annoying that he consistently refers to the IPL and other franchise cricket as being the ‘heights’ or at the ‘top’ of the sport with internationals and Tests far below. But then again, as a fan predominantly of Test cricket, he no doubt considers me an ‘indoctrinated border guard’.

“The truth is the game of cricket has never been more popular or more diverse. The cynics out there might turn towards India in that regard with its 800m fans and the vast majority of all revenues in the game and say that its extraordinary powerhouse is distorting the picture. That is untrue. While the Indian juggernaut is only just gaining pace, its economy is due to pass that of the USA in just 17 years’ time, perhaps the real successes lie currently far away from it.

Let’s take Afghanistan, for instance. In 2008, Afghanistan won the ICC World Cricket League Division 5 title in Jersey. Just a year later, by 2009, they had furthered that by beating the likes of Uganda and Argentina in winning the 3rd Division title. They were given ODI status in 2011, and in June 2017 (less than 10 years after winning their Division 5 title) they were given full membership of the ICC and with it the golden ticket to play Test cricket. While that journey in itself is mind-blowing, just pause for a moment to reflect on the fact that 99 different countries have taken part in men’s international T20 cricket, and 63 countries the women’s equivalent.”

Saying that cricket globally is more diverse than ever is an interesting suggestion but is very difficult to quantify, much less prove. Virtually every one of the 99 countries Strauss mentions has been playing international cricket matches and hosting club competitions since the early 20th century. The key difference between then and now is that we in England are often able to watch those games thanks to the invention of streaming. The sport may or may not be more diverse and widespread around the globe, but our awareness of cricket happening outside of the main ICC members has increased exponentially in the past decade.

It is interesting that Strauss uses Afghanistan as his example of success in this regard. The Afghanistan Cricket Board has refused to support women’s cricket in their country, even before the Taliban took control in 2021, which has ultimately led to Cricket Australia refusing to play against them this month. Fielding a women’s team is supposed to be a minimum requirement for full ICC membership, and this policy could lead to Afghanistan being barred from international matches altogether in the near future.

“There have never been more women and girls playing the game in this country than there are right at this minute. Over the last three years alone, the number of women and girls teams in this country has grown by a third. We now have 80 full-time professional cricketers in England and Wales, and over 270,000 people attended the second season of the women’s Hundred. This growth domestically has been matched in other parts of the world, with India in particular really starting to embrace the opportunities to grow the women’s game with the overdue advent of the women’s IPL. Also, who can forget the extraordinary spectacle of Australia winning the Women’s T20 World Cup final in front of 86,000 adoring fans.”

Yes, the growth of the women’s game is an unadulterated good from the past few years. Sir Andrew is actually underselling the progress the ECB has produced this year, as there will be 80 full-time domestic contracts in addition to the 18 centrally-contracted England players making a total of 98 professionals.

At the same time, the ECB has often seemed to be holding back women’s cricket as much as they have been helping it spread and there is much more they could and should be doing. The average wage for those 80 domestic contracts is still less than the minimum wage for a men’s county cricketer and still leaves many talented women cricketers having to maintain a second job in order to make ends meet. The absolute lack of promotion for the Charlotte Edwards Cup means that the 270,000 people who watched the women’s Hundred are almost certainly not aware of a T20 competition featuring most of the same players taking place on their doorstep. This year’s edition of The Hundred features no women’s matches in the ‘headline’ timeslot for the first time in the tournament’s short history. The ECB is singularly failing to embrace opportunities to grow the women’s game, as Sir Andrew might say.

“Whatever side of the fence you’re on regarding the sanctity of Test match cricket, no one in their right mind could challenge the assertion that T20 has helped the game of cricket in its purpose to connect people, by bringing disparate nations together, and in doing so entertain and engage with diverse players and supporters alike. That is, of course, if you agree that this is the purpose of the game.”

I mean, it hasn’t. Australia refuse to play against Afghanistan. India refuse to play against Pakistan in bilateral series. Afghanistan refuse to play against any women at all. The present possibly represents the least harmonious moment in international cricket relations since South Africa’s readmission in 1991. At the same time, the IPL owners buying up almost every T20 franchise team going means that almost every country’s domestic premier competition looks identical with the same team names, the same kits, the same pitches and many of the same players. The sport as a whole has never looked less diverse.

Also, the idea that you could only disagree with the Strauss’s premise if you believe that Test cricket is sacred is a blatant straw man argument. I prefer Test cricket to the other formats (and other sports) because I’ve watched them all and I like what I like. There’s plenty about it I would change, given the opportunity. Just because there are Simon Heffers and Henry Blofelds in the world who oppose change or progress almost on principle, there is no need to lump all Test fans together like this.

“Even the IPL salesman with the most slippery of tongues and smooth sales technique would not have been able to convey just what an extraordinary success the tournament would develop into. As it stands, the IPL sits just behind the NFL in the USA as the most valuable sports tournament on a per-match basis. It far exceeds the Premier League football in this country and, as the Indian economy grows, it is expected by the time it reaches parity with the size of the USA economy in 2040 the value of the IPL is likely to be six times what it is today. i.e. This is going to be the biggest domestic sporting tournament in the world, bar none.”

To use Strauss’s own words from earlier: “The game of cricket can’t just be about winning or, as many people paint it out, to be about pounds and pence, dollars and quarters”.

“If you allow yourself to keep bound up in the thesis of the purpose of the game is to bring diverse people together, whether playing or watching, and allow cricket to educate and connect then surely the rise of franchise cricket is one of the great steps forward. More players are playing in different parts of the world, experiencing new places and meeting new people. The game has developed and innovated at a pace never before experienced, and more and more game are engaged with the great game that we love so much. Yes, there is a danger of overkill and some tournaments seem to engage more than others but you could probably make that argument about international cricket or county cricket with its endless treadmill, or even club cricket for that matter.”

So county cricket is an ‘endless treadmill’ which should be cut back as a result, according to Sir Andrew Strauss. At least it is impossible to argue that this conflicts with the High Performance Review he published.

More broadly, I think that it is becoming clear that Strauss does not really seem to enjoy cricket. He was good at playing it, and it has been his job for almost thirty years, but he seems to loathe watching it and simply can’t fathom why other people would want to. His ideal format appears to be that each country plays cricket for one month a year in a glitzy T20 competition, leading to the the best players reaching the IPL. For fans of American sport, this will be reminiscent of basketball, baseball and/or ice hockey around the world.

Strauss’s swipe at club cricket will worry a lot of people too, considering how influential he has been within the ECB. Clubs typically attempt to play as many matches as possible because that is how they derive their income for the year. Player fees, selling food and drink, even ticket sales on occasion, without which the amateur game would die at an even faster rate than it is currently.

“And as for the women’s game, the rate of growth will just accelerate. The first IPL franchises have been sold for an earth-shattering sum of £465m. Women’s cricket is truly standing on its own two feet and is likely to be in the top three sports for earning potential for any young girl with talent and an ambition to play sport professionally.”

Women’s cricket in England would be entirely self-reliant and profitable now if the ECB were simply to fairly distribute the revenue from The Hundred. The women’s competition provided 70% of the men’s attendance and a 49.4% of the TV viewership in 2022, which are the two main sources of income. In spite of this, women players are only receiving 25% as much money than the men, and all ‘profits’ are distributed to the men’s game via the counties. This doesn’t even begin to consider the commercial power of the England women’s team.

It bears saying that the exponential growth of women’s cricket, in England and globally, strongly suggests that there has been strong latent demand all along. People have wanted to watch it, and pay for it, but governing bodies such as the ECB have simply not allowed them opportunities to do so. Even the success of the women’s Hundred was a colossal fluke. Every match being a doubleheader, meaning all women’s games would have full television coverage, only occurred because COVID and the need for ‘bubbles’ meant that it made sense to consolidate things at fewer grounds. The original fixture list for 2020 shows that the women’s teams were only scheduled to play nine matches at the eight main grounds.

“If the pioneering mindset employed by the England team under Stokes and McCullum rubs off on others, who is to say that a fair proportion of all these new players and supporters entering the top of the funnel don’t gravitate down to watching and playing Test cricket as well?”

A theme running through this piece is Strauss’s belief that love of T20 will translate to a love of Test cricket if the scoring rate is quick enough. Just as slow scoring is not really what I enjoy about Test cricket, I have enough respect to understand that people who prefer T20 are not that shallow either. Scoring at 4.77 runs per over rather than 3.97 (England and Australia’s scoring rates since McCullum took over) is not suddenly going to persuade someone who wants their cricket in three-hour portions.

The key thing about Bazball, what will bring new fans to the format, is winning. Everyone likes a winner. This is why football teams like Manchester City have more glory-supporting fans in London than they do in Manchester.

“Of course, there are bound to be losers whenever there is significant change and disruption. You only have to look at the horse salesmen at the advent of the motor car or the likes of Kodak at the advent of digital photography for some cautionary tales to emerge. It is inevitable that some old institutions might creak at the seams, including some debt-laden national governing bodies and professional clubs. Their role and purpose in the game may have to be redefined and clarified over time. Also, bilateral cricket in the way we see it today is likely to be squeezed in one way, shape or form. Is that a problem? Only if we hold on too tightly to the way things have always been. I firmly believe that the Test series that capture our imaginations today, the ones we really look forward to, aren’t going anywhere. But as we’ve already heard from John Woodcock, cricket has never been what it was.”

This section of the speech might as well have been delivered by Lord Farquaad, the villain from the first Shrek film. In that seminal movie, the evil lord sends several knights to their certain death by saying “Some of you may die, but it’s a sacrifice I am willing to make”. Strauss seems equally eager to see the end of both international and county cricket as we know it, with the surviving cricket fans left mainly with overseas franchise competitions.

I would guess, when Strauss says that “the Test series that capture our imaginations” refer to the ones against India and Australia. Can a sport, or a format, survive or thrive with only three teams and home series every other year? It is worth remembering that Test cricket is currently responsible for well over half of the ECB’s total revenue. Most of the Sky TV deal and most of the ticket sales. Lose that, and the ECB could well drop back into the host of cricket boards financially dependent on India and the BCCI in order not to go bankrupt. Not that Strauss cares about money, of course.

“What is the role of the Spirit Of Cricket in all of this? For some reason it’s hard to imagine it enduring on the pitch in quite the same way that it did in bygone ages. Scrutiny, pressure, technology and match referees means there’s less latitude now for those acts of infamy or chivalry that define what lay either inside or outside the spirit of the game. Instead, I see the Spirit Of Cricket perhaps evolving into something quite different. If the purpose of the game is to connect, inspire and engage both players and supporters then the Spirit Of Cricket in my mind needs to act as the oil which greases the cogs. It is in essence a secret sauce that differentiates the game of cricket from all the other sports, pursuits and activities out there. Of course, this has always been the case, to some degree. The Spirit Of Cricket, or absence thereof, has either elevated the game from the rest in some way or relegated it back to the vast snake pit that is elite sport, where every sinew is being strained to gain an advantage.”

I would argue the completely opposite point, that “straining every sinew” is actually the “secret sauce” that gives all sport greater meaning. As cricket fans, we can tell when it matters to a cricketer whether they win or lose a game. Just compare the reaction of players when teams lose an Ashes series to losing in the final of a franchise competition. “Straining every sinew” to win because all 22 people on the field care about the result is ultimately what causes cricketers to decide to do something they know will be unpopular but within the rules, such as Greg Chappell demanding an underarm ball in the 1981 World Series Cup final. And it also allows for the moments of chivalry Strauss enjoys, as players willingly risk their odds of victory because they don’t want to win the ‘wrong way’ or console their distraught opponents after the match.

“As we navigate our way towards this brave new world, we’re all going to have a responsibility to ensure that the spirit of the game accompanies us on this new journey. From a player’s point of view, there will clearly need to be an awareness that the world is watching every move they make, in a way that was never the case previously both on and off the pitch. With more opportunities and rewards comes more scrutiny and intrusion. While in the past players might have been able to swallow the odd invisible pill, these days they are likely to be in short supply. In addition, the best players (wherever they hail from) will have to weigh up their own personal aims and ambitions alongside their loyalty to their own counties and formative teams. This may lead to some hard soul-searching to be done but, in the name of the spirit of the game, it must be done.”

I think Strauss massively overestimates the visibility of current English cricketers. When Ben Stokes and Alex Hales were arrested following a fight in Bristol, it took almost two days for the story to be reported by the press. No one involved seemed to know who he was, or at least think he was famous enough to sell the story to the tabloids. If Jos Buttler walked into my workplace tomorrow, I genuinely don’t think any of my colleagues would recognise him.

There have certainly been examples of players turning down lucrative T20 contracts, although every example I can think of was in order to play for England rather than purely through loyalty to their county. Loyalty does not pay the bills, and these are professional cricketers. Emphasis on ‘professional’. This is their job, and most cricketers only have a few years of maximum earning potential before teams move on to someone younger. Suggesting that people who look at their personal circumstances and take the highest offer are in some way betraying the Spirit Of Cricket is neither fair nor right.

“Perhaps more important, the Spirit Of Cricket needs to accompany modern players (and I’m speaking primarily about players in the men’s game now) to an area that neither the prying eyes of the media or the feverish adulation of fans can penetrate, and that is the dressing room. As we move forward as a game, with players of different genders, races, creeds and beliefs coming together, so the traditional macho hierarchical and perhaps at times verging on bullying dressing room banter of yesteryear will need to be softened to a culture that is more tolerant, understanding, welcoming, and embracing of difference. The events over the last 18 months, whether they come from Yorkshire or elsewhere, have shown we’ve got a lot of work to do in this area, but the Spirit Of Cricket demands that we do this work.”

For a start, the issues of racism and other discrimination are certainly not exclusive to men’s cricket. Ebony Rainford-Brent and Isa Guha have both described their own experiences of racism whilst they were players, at least two current women’s cricketers have been punished for discriminatory social media posts, and the continued lack of representation of Black and Asian players in the women’s professional game (even compared to the men) suggests something has gone very wrong in the junior pathways.

Besides that fairly critical error, this whole section portrays someone with very little understanding of the problem of discrimination, nor empathy for the people it happens to. Every part of his description seeks to minimise the issue. It doesn’t happen to women (it does). It is “traditional”, “macho” and “hierarchical” behaviour (rather than unacceptable, abusive and exclusionary). It is “verging on bullying” (rather than being one of the clearest indications of bullying known to humanity). It is “dressing room banter” (instead of being considered unlawful in every other UK workplace outside of cricket). That endemic racism in terms of recruitment, retention and regular insults is a culture that needs to be “softened” (not eliminated entirely).

To put this in context: It is likely that Sir Andrew has taken part in several programmes intended to educate people about discrimination and both its legal and emotional outcomes in the past couple of years as an ECB employee. Reports have been all over the press. Despite all of the information available to him, all of the training, he just does not seem to understand the problem at all.

“For someone who’s probably already spent too long in cricket administration, I see both huge challenges and opportunities for those running the game. The game’s spirit dictates administrators need to seize this moment of disruption and change, and ensure that it leads to the game fulfilling its purpose to connect, entertain and engage. That means an administrative equivalent of Bazball, a pioneering, forward-looking, optimistic mindset that keeps the intention of what success in this game really is at the front and centre of their minds. If we allow ourselves to be weighed down by the way things were, we run the risk of creating division and infighting and battles for control. The various national governing bodies might well find themselves as the last horse salesmen in the era of the motor car. We need to let go of those dirty words like ‘power’, ‘control’, ‘politics’ and ‘ego’ and just simply ask what we can do to help the game fulfil its purpose.”For someone who’s probably already spent too long in cricket administration, I see both huge challenges and opportunities for those running the game. The game’s spirit dictates administrators need to seize this moment of disruption and change, and ensure that it leads to the game fulfilling its purpose to connect, entertain and engage. That means an administrative equivalent of Bazball, a pioneering, forward-looking, optimistic mindset that keeps the intention of what success in this game really is at the front and centre of their minds. If we allow ourselves to be weighed down by the way things were, we run the risk of creating division and infighting and battles for control. The various national governing bodies might well find themselves as the last horse salesmen in the era of the motor car. We need to let go of those dirty words like ‘power’, ‘control’, ‘politics’ and ‘ego’ and just simply ask what we can do to help the game fulfil its purpose.”

Strauss’s mindset has always been that of a business executive. Such people love nothing more than launching a vast, ‘game-changing’ project which leaves a mark on their company. A bold initiative which will revolutionise their field. For Tom Harrison, it was The Hundred. The attraction of this approach is that there is literally no downside for the person responsible. It it works, they are hailed as a hero and become legends in their field. If it fails, they receive a huge severance cheque followed by a job at another company soon after. It’s like gambling with someone else’s money.

A great executive, a great sports administrator, should ideally be completely unknown and unheralded. I yearn for the days when I had no idea who the chair and chief executive of the ECB, because I only really became interested in the inner workings of English cricket due to my frustration with endemic failures of management. It’s like umpiring. When an umpire does well, you remember the match. When an umpire does poorly, you remember the umpire.

“Likewise, those new powerhouses of the game (the investors, the owners, the tournament directors, the agents), they need to understand that both players and the clubs and countries that facilitate their development are not there to be exploited like minerals being pulled out of the ground. The Spirit Of Cricket demands that short-term profits and return on investment do not create barriers to the nurturing and development of the next generation of cricketing icons. Purpose-led investment, where the returns are sustainable, has to be the order of the day rather than the hard-nosed, Gordon Gecko-like ‘greed is good’ attitude. If the purpose of the game is to bring people together, connect nations and expand the reach of cricket, then investment in the grass roots of the game cannot afford to be so inequitable.”

Can anyone think of an example where a billionaire has forgone hoarding their assets in order to ‘give back’ to society in any substantial way? It’s not entirely unheard of, but it is extremely rare. Relying on the generosity and benevolence of the super-wealthy and the Gordon Gecko-like people who tend to become investors and agents seems like a recipe for disaster.

Of course, the current arrangement is a long way from offering an equitable investment in most of the parts of the game. Everything other than men’s professional cricket gets precious little money or resources, even as the commercial power of the women’s game increases exponentially and club cricket obviously provides a large number of those professional men’s cricketers. It was telling how Sir Andrew Strauss’s High Performance Review insisted that the men’s England and county teams needed even more money spent on them, which in the zero sum game which is cricket’s finances would logically lead to everyone else losing out. Far from being a proponent of equitability, Strauss has consistently sought to make the issue worse in England and Wales.

“And finally, what does the Spirit Of Cricket say to those who follow the game as it moves forward at this frightening speed. Well, largely in my opinion, it says little other than ‘Sit back and enjoy the show’. There is something out there for everyone. In the past, it could be argued that certain interests, whether they lie in this room [within the MCC], or in the corridors of the ECB and other national governing bodies, or on the boundary edges of the county grounds, took precedence over others. That is no longer the case. No one, not even BCCI, controls the game any more. There are too many people involved, too many variables, too much disruption and chaos for anyone to be pulling the strings. In a sense, the game is democratised. While this is confronting and perhaps difficult to hear for some, I feel like we should be rejoicing this fact. The game now has more freedom and more levers available to allow it to fulfil its purpose than ever before. There is genuine choice for players, spectators and followers alike. The future direction of the sport will not be decided in the meeting rooms of the ICC in Dubai, but rather the puchasing power of the increasing number of those who choose to follow the game.”

It is a fundamentally absurd proposition that moving English cricket from being controlled (theoretically) by tens of thousands of cricket fans as members to being owned by a handful of foreign billionaires represents democratisation. The status quo is undoubtedly flawed. The vast majority of county members are primarily fans of men’s first class and Test cricket, which means the interests of white ball and women’s cricket are overlooked, as is what’s best for the amateur clubs that the ECB also governs. If anything, the one structural change which would improve how English cricket is run would be widening the base of people involved in making decisions beyond the current county members. Centralising power in a handful of investors and hedge fund managers does nothing except make profit the only objective for the sport, to the detriment of everyone in the game.

“I sense that the early pioneers of the game will be looking down at these developments with a mixture of pride and satisfaction. It is genuinely extraordinary to see how far the game travelled and expanded from those early days in the rural paddocks of Kent. More importantly, it ain’t done yet as it creeps ever more confidently to influence more people in different corners of the globe. Broader cricketing communities are growing. More boys and girls are being inspired to play or follow the game, and hundreds of millions of people around the world are using cricket as a vehicle to entertain themselves and others every single day. To me, whatever our background or beliefs, the Spirit Of Cricket dictates that this is something for which we should all be extremely grateful.”

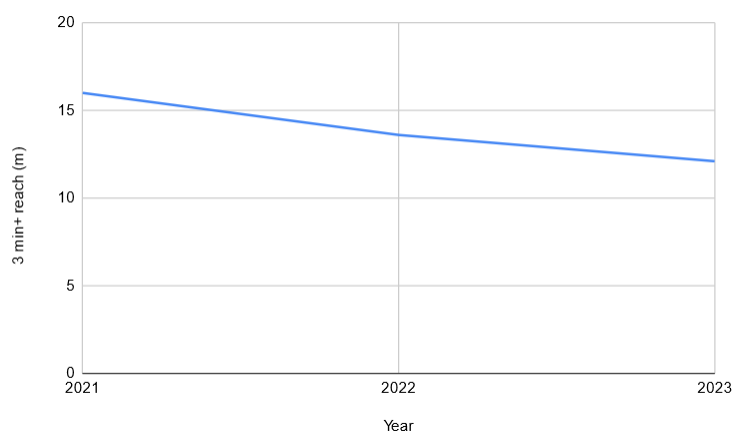

I sense that the early pioneers of the game will be looking down at the modern game and wonder why the landed gentry who were oppressing them in the 1600s had basically stolen the sport from them and been controlling it for the past 300+ years. I mean, I don’t really. I obviously have no idea what a 17th century farmhand would think about anything, but it’s a useful oratorical device you can use to make any point you want. I do know that club participation in the sport is down in England, as are TV viewing figures. I worry about the long term survival of the sport in this country, and nothing Strauss said in this long speech made me worry less.

More broadly, I think this talk speaks to a wider issues within the ECB. Sir Andrew spends a large portion of it insulting English crickets fans (who are ultimately the source of all the ECB’s income, let’s not forget), betraying his lack of awareness regarding women’s cricket and minimising the issue of racism within English cricket whilst actively campaigning for a sport run by billionaires as opposed to people who love the game. This man was in the halls of power for over seven years, where I believe he was pretty popular, wielding a great deal of responsibility and influence in the process.

I am very glad he’s leaving, but I worry that there are more people like him left behind.

If you have any comments on this, or the other stuff happening in English cricket right now, feel free to comment below.