A review of “The Breaks Are Off” by Graeme Swann.

Ah yes, nothing screams “topical” more than a book written in the glow of the 2010/11 Ashes success and a blogger reviewing it because he only just got around to reading it. I have no idea when I bought it, and no doubt when I did, I paid nowhere near full price. This is the hardback version. If you feel so inclined you can purchase this for 1p plus postage and packing on Amazon, so it’s not as if you are going to be out of pocket if you purchase it and hate it. A number of you may have read it already. So why the review?

Well, I once had a discussion with my editorial committee who said that we shouldn’t really bother with this sort of thing. But as Sean and Chris are away at the moment, I thought I’d do what I want! Secondly, and I almost hate myself for saying this, it isn’t the worst book I’ve ever read. Thirdly, with the power of hindsight, and the subsequent events, there’s some interesting stuff in there. When you consider this would have gone through the ECB powers-that-be to get to the press, some of it is remarkable. Fourthly, the book is recalled by many for his slagging off of Kevin Pietersen as captain – he really doesn’t do that too much (the effing bowl effing straight was as juicy as it got, and he pointedly doesn’t take sides in the Moores v KP debate, except to say the latter wasn’t a great tactical captain which I’m not sure even his most ardent fans could say there had been evidence of). Fifthly, I’m on a roll with content, so let’s go for it.

Swann has his own little nickname on here – Lovejoy – because there’s rarely been someone so cocksure in his own laddish hilarity than the erstwhile host of Soccer AM, subject of one of the all time great book reviews, and now, for reasons best known to the Beeb, employed (or was employed) on a cookery show. Graeme Swann might as well be his twin brother. This annoying trait runs through the book like a stick of rock. Constantly on the lash, getting trashed with mates, taking the mickey out of all and sundry, he’s great when he’s dishing out the gags. When crowds remind him of his “cat under the floorboards” excuse for drink driving they are “inane” and “I didn’t hear one amusing thing”. Frankly, if, as he said, crowds meowed at him as he came to field near them, I’d be laughing my socks off. Maybe japester Swann might one day get it. I have no idea how a bullying culture might have developed.

The book takes the usual route. Boring bits about childhood that no-one really wants to read (OK, some do, I don’t – it’s either awwww shucks I’m so lucky, or I was really talented and was only a matter of time before I was found out) and so many times I’m put off reading books like these because I have to plough through the tedium. Once Swann gets his breaks, he encounters a couple of road blocks. The first was his calling for England in the Fletcher / Hussain rebuilding series, where he confesses he didn’t take it the way he should have, and his comments on his ODI debut are very revealing:

He’d been given a time-keeping warning during the test series, Gough had given him that punch (not a lot of insight on that incident) and Swann had just wanted to go home. The treadmill of international cricket, especially when you are not playing, must be very harsh. I think it speaks volumes of how the team ethic was in those days. Nasser was a captain imposing himself, there were a number of former captains in the team, and it was a tough place for younger, newer players. Again, the events from further down the line, when Swann was the senior player, seem remarkable given the troubles he’d had earlier on.

Swann really gives it to Kepler Wessels as a coach, which hasn’t been disproved by subsequent events. Wessels comes across as a weapons grade bully, confusing being tough with being a dick. Swann may not be the most reliable of witnesses, but it’s certainly the feelings I’ve heard from that time. Swann decided to move on to Notts and played reasonably well, got noticed by the selectors and made his second ODI debut on the tour of Sri Lanka where England somehow won the series 3-2. Test honours followed on the tour of India in 2008, or at least they were likely to be until the horrific terrorist attack in Mumbai.

There’s an excellent part of the book where you feel Swann had major issues to contend with. Recently “partnered up” he was reluctant to return to India. A conversation with his dad, who comes across as a right no-nonsense sort of bloke, like Competitive Dad, basically said “this is your chance to be a test cricketer. I think you will be safe, but we will all be worried while you are away, but put yourself first. This is what you always wanted.” I think it’s one of the best parts of the book.

“What on earth were we doing even thinking about playing cricket when the hotel manager and his wife, a couple who had looked after us so well just days earlier, had been executed in the lobby of the Taj?”

It’s always easy for us to judge. But this is pretty powerful stuff.

Here’s one of the parts that I thought “how did you get this through the ECB censors?”

and the quote:

“Because Giles Clarke had been so adamant about us staying put, and that there was no danger to us whatsoever, I had anticipated that we would be asked to go back from the moment they confirmed us on the flight home.”

And his reaction to being called a sporting hero by the Prime Minister:

“…if I am 100 percent honest, there was no show of solidarity from me. I went to receive my first England Test Cap when there was a threat it would never materialise otherwise.”

You have to give credit for the honesty.

There’s not a lot of sympathy for other players, Monty especially, for being elbowed aside, but then when we are talking about elbows, his discussions on how he was made to play on when his elbow played up in West Indies (god, that was an awful link). Play through the pain, damage it more, an injection or two, and we’ll repair it in your spare time. Oh, and we’ll tell a story about a well-meaning religious man who loved cricket, just for laughs (he was working at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota). It does give you a brief insight into how the sporting personality can work.

We have how great it was to win the 2009 Ashes. How great it was to take the final wicket. How Swann batted in only one way – the way he plays, and how difficult it was to block at Cardiff when it was needed. Swann goes on a moral crusade when it comes to the Pakistan tour of 2010 – there was always something about Butt he didn’t like and Amir should have definitely been banned for life and that if he came across him again he would give him some – which is fair enough. We always moan when players spout platitudes, and yet when they comment we say they should shut up. Argue the point, not the man, even if he is Lovejoy!

There’s a story about how the players finished their season against Pakistan and booked holidays. Swann was off to Las Vegas, as was Stuart Broad for Luke Wright’s stag do, until they were told to cancel for a four day boot camp in the German countryside. Swann tells you precisely what he thought about this old drivel, in two pages of barely concealed contempt.

The “he” in this particular text is Andy Flower. However, on the next page Flower is said to mutter “What the hell am I doing here? Why did I agree to this?” Our Ashes prep had been put together by our security advisor, Reg Dickason, so maybe that’s why he’s above Lawrence Booth in the power list. If he’s strong enough to get the England lot to buy into this team-building nonsense, then he needs a higher ranking. The bloody team psychologist went on it – we know because Swann lets the reader know he’s a bad snorer – while the security guy plonked himself in a lovely hotel! It’s a wonderful insight into the garbage an international sportsman has to go through. Then it gets even more silly when they matched Jimmy Anderson with Chris Tremlett in a boxing match, and the man mountain injured Jimmy. I mean, if this is true, you can pretty well understand why the likes of KP, and Swann, found the regime humourless and oppressive. It’s an interesting four pages into the one-sized fits all world of modern sport.

The Ashes makes up the end of the book. Lots of good times, Perth brushed over a bit. But to me the interesting section is this, especially in hindsight and the handling of the individual subsequently:

It makes you wonder. Love him or loathe him but Swann had the attitude for test cricket. Accentuate the positive, self-belief, relish the moment when it arrived. Once secure in the team, he was, along with Prior, the main mouth against the oppo. We don’t like it, but that attitude was very much part of that team. It also meant that it was not bound to last. But Finn, who was told too many times what he couldn’t do, told that England’s strategy of “bowling dry” was not something for him, and with the presence of Tremlett looming, worried about what he hadn’t done. What hadn’t gone right despite the figures. It’s quite revealing the difference between secure player who can’t understand how an insecure player perceives his own performance, and the insecure player feeling worried despite a result the secure player would sell his grandmother for. Really interesting (well, to me it was).

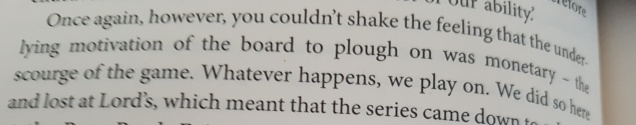

The book has digs at ODI series not meaning that much to the players, and there’s the reminder that the current regime is only following those of the past when he said that England were scheduled to play Ireland the day after the 2009 Ashes was scheduled to conclude (Strauss opted out of that game, but a lot of the main men went). Then there is the “what the hell are you doing here when there isn’t an Ashes series” 2010 matches v Australia in England. Swann lets it go:

“Everyone wants to play in England v Australia matches, although the one-day series we played against Ricky Ponting’s team in midsummer 2010 was naturally unloved. The five-match campaign was no more than a money-making campaign and nobody was fooled by it. As players we couldn’t escape the feeling that instead of a NatWest Series we could all have been enjoying a fortnight of rest and recuperation at the halfway point of another hectic year.”

I’m not rushing to find out what he might think of the current series.

Here’s another “how did this get through the ECB moment” after the Pakistan accusations over England throwing an ODI:

It’s quite a decent read all told, if you can suspend the loathing he inspires on here. There’s enough to get your teeth into, and is worth the pick up for shirt buttons on the secondhand market. You do get the impression that if he was in ice cream he’d lick himself, but he’s not boring in the book. Give it a whirl.

For nonsense like this:

Hope you liked this. Got a lot more where this came from. Some of the old Bob Willis books are treasures. Real treasures. More reviews in the down days before the Ashes – unless my editorial colleagues want to go on a boot camp somewhere and beat it out of me.